The Lady and the Unicorn Tapestries. c1500. Maison de Cluny Paris.

Iris Murdoch was born on the 15th July 1919 and she published 'The Unicorn' in 1963. It was her seventh novel. It’s a magnificent set piece, combining elements of myth and fable with concepts of duty and honour, punishment and retribution. The physical setting of the story - a country house in remote part of Ireland between the Burren and the Cliffs of Mohr, is the theatre in which the tormented characters to play out a drama which moves inexorably to a dramatic and ghastly conclusion.

The usual elements of a Murdochian tale are present - self inflicted punishment, ambiguous sexual desire, an innocent catalyst who precipitates disaster, agonies of indecision about moral duty versus personal fulfilment. The ‘unicorn’ of the title is Hannah, a devout aristocratic woman living under house arrest at the behest of her absent husband after he discovers her infidelity and she tries to kill him. Various odd characters are beguiled by her situation and a chain of events leading to a deadly denouement are precipitated by Marian, a young woman who arrives to be Hannah's tutor-companion. The novel has the same sort of Gothic atmosphere as 'Jane Eyre', another tale of an innocent young woman finding herself in a lonely house, surrounded by the dark forces of madness and desire.

I read 'The Unicorn' about eight years after it was published. The summer vacation between school and university I got a job at a country house hotel in Wales. I responded to an advertisement put up on a noticeboard in the small Welsh town in which I lived and after a brief correspondence I was offered a post as general helper and assistant cook. One bright Sunday morning my father drove me for miles down ever narrowing lanes and left me with urgent exhortations to phone home if it didn’t work out. I carried my suitcase up a winding drive to a Georgian house with a granite facade and a huge garden.

My bedroom was tiny and looked over the yard where the dustbins were kept. I was informed by the supercilious young man who guided me there, that it was normally used for the chauffeur of any guest who brought 'staff'. He (let’s call him James) made me feel that my occupation of it might prohibit such august persons coming to stay. The cook was a severe older woman who made country house type meals and produced vast quantities of washing up that it was my responsibility to deal with. A bit like a nurse in an operating theatre, I had to second guess her needs and produce on the instant whichever utensil she demanded in order to spatchcock a chicken or brûlée a crème, neither of which I had ever seen before. It was a long way from my Mum's liver and onions.

I don’t remember there ever being any guests. People often came for dinner and the owner usually ate with them. The cook served up elegant suppers of a style that might have been fashionable in the nineteen thirties. I learned how to make béchamel sauce and coq au vin. There was savoury course at the end of the meal - dainties like angels on horseback or triangles of Welsh rarebit garnished with diced tomato.

The days went by and I still could not make out how the place operated. One afternoon a jolly couple drove up in a Morgan sports car and asked if we had a room. James told them we were full. He marched back into the lounge where we were polishing the woodwork with beeswax and announced that they didn’t look like 'the sort of people' he wanted staying there. I was young and green enough to say that they looked alright to me, only to be sharply informed that it was not my business.

Apart from my kitchen tyrant, there were two other staff members; a Japanese girl who spoke very little English and the housekeeper, a woman in her late thirties who said she was in hiding from her diplomat husband for reasons only darkly hinted at. James performed no obvious function except to criticise our efforts in keeping the place clean and fit for guests, should they ever arrive.

The owner was a man in his sixties, handsome in a thickset sort of way. He was cultured, elegantly dressed and quietly spoken. The hotel was a treasure house of his books, pictures and delicate furniture. Two wonderful Murano glass chandeliers hung in the drawing room, their droplets made not of crystals but of exotic hanging fruit. In my dreams I own a pair of these.

Purple grapes and red plums chinked and tinkled in the breeze when we opened the windows. Maybe I had been reading too many French novels but I felt that the atmosphere in the house was electric with unspoken tensions and unresolved mysteries. James and the owner lived in a suite of rooms I was not allowed to enter and I was shocked when only one set of bed linen emerged on laundry day. We were only four years after the Sexual Offences Act and such things had not come my way before.

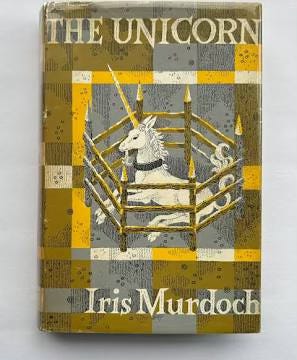

The work was not arduous and often in the afternoons I would find a quiet place in the garden to read. I was going through a phase of reading André Gide and François Mauriac but one afternoon I found on the shelves in the library a hard back book with a grey and yellow dust cover showing a unicorn enclosed in a sort of wooden corral. 'The Unicorn' by Iris Murdoch. I’d heard of her and I fell on it.

The atmosphere and setting of ‘The Unicorn’ has stayed with me through the years but I found it puzzling at the start. There is an element of the fantasy about many Murdoch novels, and 'The Unicorn' certainly didn’t reflect any sort of real life I had ever come across. Of course it’s not meant to, Murdoch uses the novel to explore ideas of power, morality and personal fulfilment. André Gide's short novel 'La Porte Etroite' covers similar territory and I had studied that for my recent French A level, so gradually the themes of ‘The Unicorn’ began to make sense. Incidentally, Iris Murdoch mentions André Gide in a letter to Jeffrey Meyers in 1979 and denies that he influenced her. 'I never developed any concept of him' she said.

Murdoch plotted her books in minute detail, every scene had to earn its place in the narrative. She knew what her characters were going to do in order to play out her plot. From a writer's point of view this is a fascinating discovery. Murdoch's characters are not captive in some sort of novelistic laboratory. She doesn’t create a scenario and then let them loose to see what happens, she plans it. This approach is clearer in 'An Unofficial Rose' published a year before ‘The Unicorn’ where every character is so interconnected that the story plays out like a chess game.

Back at the hotel things were not going well. James’s behaviour became more hysterical. There were angry scenes barely concealed behind closed doors. We girls tiptoed around like mice and still there were no guests. I retreated to the kitchen as much as possible. I moved on from béchamel sauce to roast duck and syllabub. When I was off duty I hid in the wild part of the garden and read ‘The Unicorn’.

Then one day the penny dropped. I was living in an Iris Murdoch novel.

Let’s call it ‘The Venetian Candelabra’

A man from a wealthy family becomes a Catholic priest but his taste for luxury and his homosexual desires precipitate a crisis and he leaves the priesthood. Was the banishment voluntary or insisted upon? We don’t know. He buys a remote and beautiful house where he can be surrounded by his books and his objets d’arts. There he lives quietly and discreetly with a series of young men who once their bloom has tarnished, are banished from Eden with much tears and gnashing of teeth. One young man refuses to go quietly. The minor characters in the story have their own reasons for being there. Domestic violence can happen anywhere and its more genteel victims scan 'The Lady' for positions as housekeepers and companions - positions that provided a home as well as an income. A young woman might cross the world to escape from family pressures to conform to cultural norms. An elderly widow of limited means might use her culinary skills to keep in touch with the class into which she was born. A naive young student observes all but with limited understanding.

How does the story end?

The housekeeper runs away after an assault by the young man. The enigmatic Japanese girl stays. The young man is driven to the railway station in tears. The cook becomes even more tightlipped, the former priest deals with his guilt - or not. The young student rings her father who whisks her back home and she spends the rest of the summer working in a lawyer’s office.

François Mauriac said "Tell me what you read and I'll tell you who you are is true enough, but I'd know you better if you told me what you re-read."

I’ve read ‘The Unicorn' three times now and a lifetime later, it seems a lot less fantastical. People really do get themselves into the sort of situations that novelists dream of. We live our lives with conflict and dilemmas, we hide emotional truths from ourselves and our loved ones. We compromise and obfuscate, and we can be paralysed by indecision. Iris Murdoch's genius was to dissect the inner lives of her characters and lay them out for our forensic examination. It just takes maturity to realise that life can resemble art more than we ever thought possible when we were young and green.

Footnote. Wikipedia says of the Lady and the Unicorn tapestries pictured at the top "It is now (generally) agree that they present a meditation on earthly pleasures and courtly culture, offered through an allegory of the senses."

Exactly.

Llynderw Hall (it’s now a very upmarket holiday let) features in a book called ‘Country Cuisine’ by Elizabeth Kent published in 1980, not long before the hotel closed. This is the recipe as it appears there. I’ve shortened the instructions.

Prawns in Rice with a Nice Sauce. For 4

½ lb prawns

1oz butter

I tsp olive oil

3oz cooking brandy

¼ pint double cream

Pinch grated nutmeg

½ long grain rice

2-3 strips of red pepper

A few black olives chopped

2oz gruyere or emmental.

Cook the rice until almost soft. Season and lightly sauté the prawns. Set aside. Heat the brandy and ignite, shaking vigorously. Add the cream to the pan, season with the lemon juice and nutmeg. Take 4 individual gratin dishes and divide the rice and prawns into each. Add strips pepper and chopped olives and pour over the sauce. Top with the cheese and grill lightly. Serve immediately with a crisp green salad.

Thoroughly enjoyed this - the writing, that is, still abed so not a prawn in sight ! Tried Iris M, but she wasn’t my cup of tea - not a patch on you.

What an extraordinary tale. Like you I devoured the early novels about the same time and loved them so much that I have not reread them in case they do not hold the same magic. Her descriptions of food in her books is so telling of character and you may have a whole series of posts based on their choices - though I am not sure how much of it you would want to eat! A wonderful, rich piece to start the day.