The Secret Garden

Frances Hodgson Burnett's masterpiece and a post for National Gardening Week.

In time gone by did seasons come and go?

And was there summer rain and winter snow?

Perhaps! What matter? Now the violet’s blue

The roses red - and friends are tried and true.

From ‘A Woman’s Reason’ by Frances Hodgson Burnett 1849-1924

Many years ago, after my father died, I found amongst his things a tiny photo of me aged about four. It shows me in his greenhouse in front a bench loaded with pots and wooden trays of seedlings. I am wearing a hand knitted cardigan and a plastic slide holds back my unruly hair. The image catches me in mid sentence, gesticulating and enthusiastic.

I don’t remember the photograph being taken but I do remember often being with Dad in the greenhouse and standing beside him at the end of a gardening day whilst he scrubbed his hands. I was an only child then and I was my father's shadow.

As a young man in the late 1920s, after a long day as an office boy in a soap factory, my father went to night school and trained to be an accountant. Night School was the only way for working class young people to get further education in those days, and for him accountancy was an ideal profession. He was good with numbers and he liked detail. Those seedlings were meticulously spaced out. Later when we gardened together, we teased each other about my love of large horticultural gestures and his passion for growing alpines in terracotta pans. His tiny plants glowed like miniature jewels, my fragrant, blousy chaos drove him mad. Our gardening styles reflected our personalities.

So my love of gardening definitely comes from my Dad but it also comes from Frances Hodgson Burnett’s perennial children’s book ‘The Secret Garden’. By the time I read it when I was about seven, I already considered myself a gardener

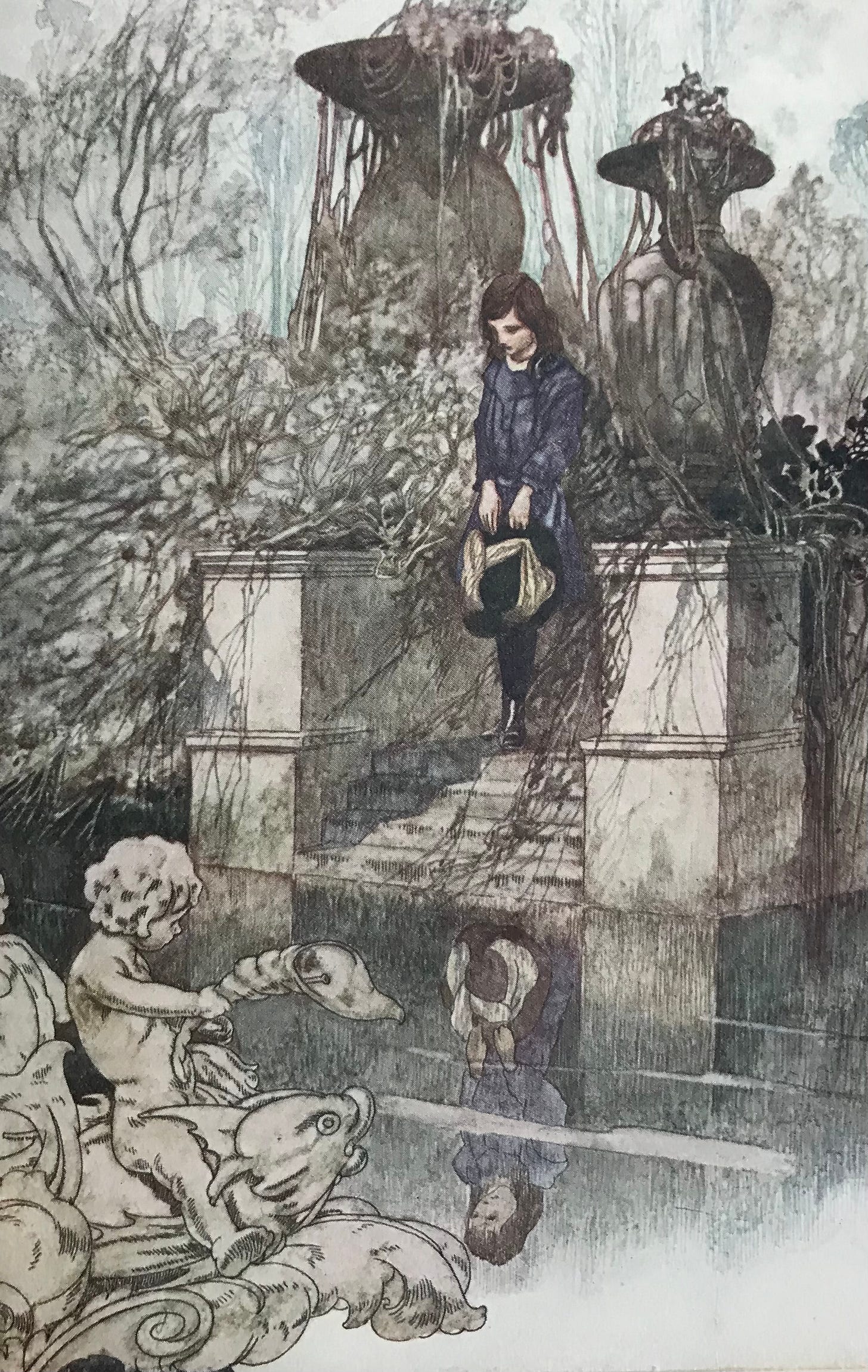

.When Mary Lennox crouches down in the secret garden to free the emerging snowdrops from the weeds, I immediately knew that she was doing the right thing and that I would have done the same. When she asked her Uncle Archibald Craven if she might have 'a bit of earth’ I was right behind her, and when Dickon brought the tools and the seeds, I was ready with my gardening apron to knuckle down and get planting.

There are some beloved books are there not, where your connection to them is so profound that you are deeply proprietorial? They have become part of you. The fact that ‘The Secret Garden’ is set in Yorkshire where I was a child, only added to my connection with it. Even the sound of the names was familiar - Misslethwaite, Craven, Sowerby. I knew those places and those people.

The first chapter of ‘The Secret Garden’ is called 'There Is No One Left' - and it is a masterpiece of atmospheric writing. Mary is the neglected child of a British couple who die suddenly in a cholera outbreak in India. Mary’s parents are decadent and unfeeling, not unlike the Raj itself. The servants in the house have fled before the disease and Mary, finding herself alone amongst the remains of deserted dinner party, drinks a glass of wine and falls asleep. She wakes up to a new life where she is forced to move to the north of England; a country she has never known. Once there she discovers that privilege doesn’t necessarily mean happiness and that the natural world is a place for self discovery and resilience. There is a subtext about place and colonialism in the book. In India, like a plant in the wrong soil, Mary fails to thrive. On home ground she eventually flourishes.

There are those who find the 'mens sana in corpere sano' message of 'The Secret Garden' hard to take but it’s never bothered me. (Sorry Susan). Growing up in the north I was accustomed to the idea that you wrapped up warm and got outside and that outdoor activities were somehow more ‘morally pure’ than inside ones. My parents were brought up by Victorians after all.

I identified with Mary when she explores the vast and lonely rooms of Misslethwaite Manor because after huge lunches on winter Sunday afternoons, I would wander off and peep into the unused farmhouse parlours of my many Great Aunts. The adults would be engaged in boring conversations about the long dead, I’d eventually tire of whatever I was reading and I’d open the doors of dim rooms whose walls were hung with faded hunting scenes. Victorian lustres would tinkle on vast sideboards and old paisley shawls softened the backs of stiff sofas. Those rooms were only ever used for funerals. I wasn’t at all surprised when Mary Lennox discovers another lonely child in a remote bedroom at Misslethwaite.

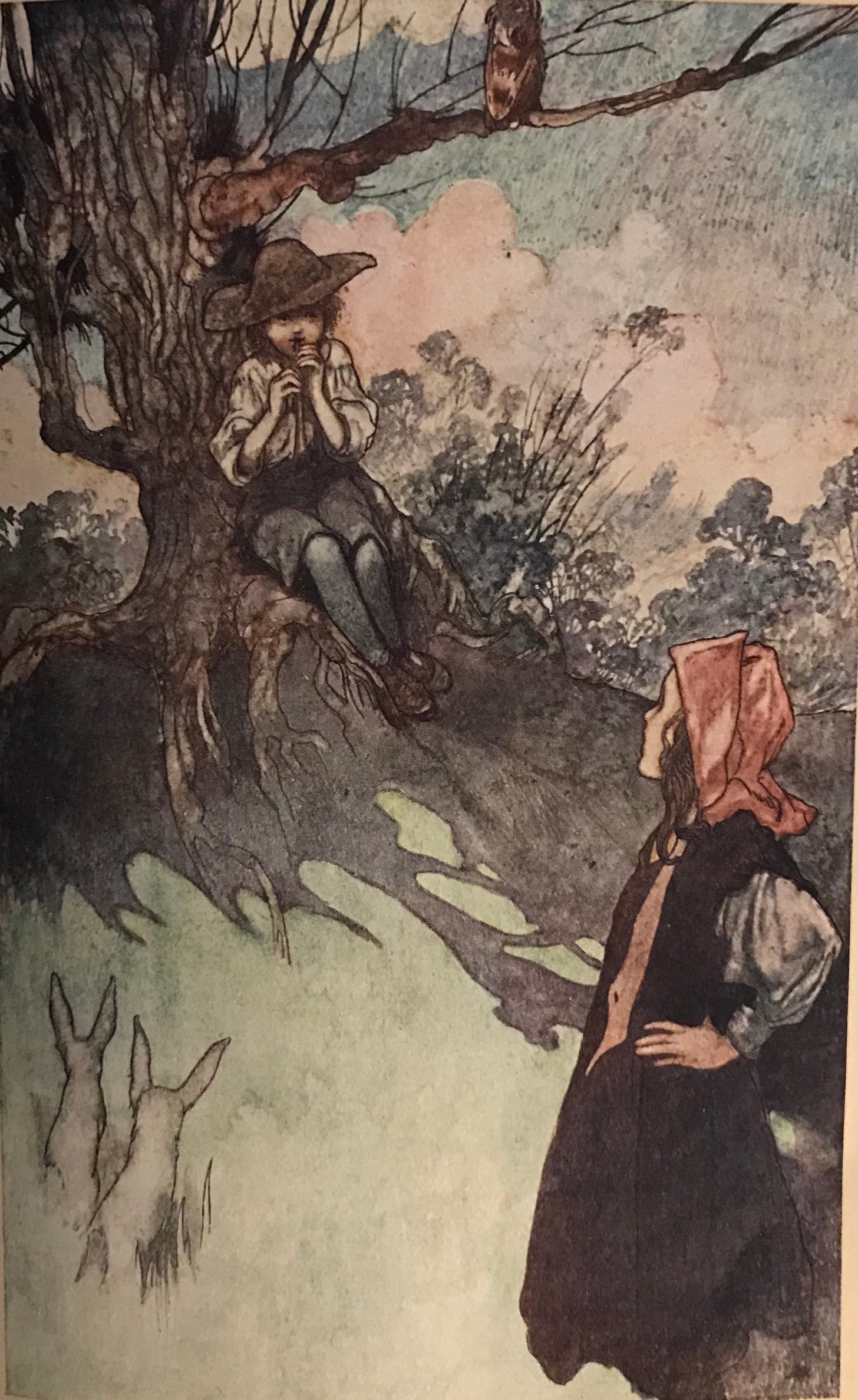

Apart from Maggie Smith as the housekeeper Mrs Medlock, I really dislike the 1993 film of 'The Secret Garden'. As an aside I just looked it up on Wikipedia to check the date and it says 'Dickon is an outdoorsy boy who is good with animals'. I nearly choked. What? Dickon is not an ‘outdoorsy boy’ who is ‘good with animals’. He is a God. He is the Great God Pan himself. There was a whole load of nonsense when the film came out about 'The Secret Garden' being about the emergence of sexuality in early adolescence. Sorry? That is absolutely not what the book is about. It's about redemption. In this case redemption through gardening.

The old gardener Ben Weatherstaff recognises in the child Mary a kindred spirit. “We’re neither of us good-lookin an’ we’re both as sour as we look” he says. Mary bridles at his northern frankness - as she does at the directness of the young housemaid Martha Sowerby. “Canna tha’ dress thysen ?” asks Martha - astonished at Mary’s dependence on being looked after. The servants at Misslethwaite are far from servile. Mary asks Martha if she is her servant and Martha says she is Mrs Medlock’s servant not Mary’s. There’s an implication here. Be self reliant, look after yourself, and you are neither better nor worse than anyone else.

There is a telling moment in that early scene. On the first morning at the manor, Martha brings Mary's clothes out of the wardrobe and Mary says crossly “Those are not mine”. She’s a nasty child and you wonder if she’s going to throw a tantrum. She looks at the dress and coat and something dawns on her “Those are nicer than mine” she says. Suddenly you know what the book is about - it’s about the rehabilitation of Mary Lennox and we haven’t even got to the garden.

It’s now well established that getting your hands dirty when gardening increases your serotonin levels. The microbacteria in the soil triggers the release of the chemical that makes humans happy. A second chemical, dopamine, is released when you harvest or pick something from your garden. Gardening is good for you. Mary, Dickon and Colin call the effect that tending the secret garden has on them 'magic'.

Susan Sowerby, Martha and Dickon's mother, is the moral lodestar of 'The Secret Garden’. She brings up happy, healthy and self sufficient children in a cottage on the moor and it is she who writes to Archibald Craven to suggest he comes home. She reminds him gently of his duty as a father and what his late wife might have wanted.

In the blindness of bereavement Archibald Craven has travelled the world and his loss has travelled with him. The end to loss can only be found in one place - home. So he returns and the magic of the garden is waiting for him too. His child has been healed by friendship and by nature, and Mary in healing another has healed herself.

I often wonder in what ways the books I re-read countless times as a child (all those quiet Sundays) have made me the adult I am. There is no one who can answer that. Not even me. But I do know that my father and Frances Hodgson Burnett’s wonderful book made me a gardener.

It is National Gardening Week next week. Time to get planting.

Threshing Scones

I’ve made threshing scones. Nothing fancy about these, they are the sort of thing that Susan Sowerby would have made for her brood of children. It’s a basic scone recipe but my great grandmother Fanny Burgess (and who knows, maybe even her mother Jane Hewson) called them ‘Threshing Scones’ becase they are made at a time when because it’s all hands into the threshing yard, there is no time for faffing with cutters.

8oz self raising flour, I tsp baking powder, 2oz butter, 2oz sugar, dried fruit if you wish, milk - I sometimes add a tablespoon of plain yoghurt.

Mix the butter into the flour, the BP and a pinch of salt, until the mix is like breadcrumbs. Add the milk until you have a soft dough. Fold over the dough a couple of times and shape to a round with your hands. I find it easier to do this on a sheet of baking parchment. Section into six or eight pieces. Bake at 200c for about 20 minutes.

These are really quick to make so you can get back to threshing - or to the greenhouse in my case.

I too read this countless times as a child, Liz, beginning when I was living (briefly) in Yorkshire, though there was no danger of my confusing my grandparents’ railway cottage in Huddersfield with anything in this book! I quite see how it helped make you a gardener, but as you are aware, it did not have that effect on me. I fear that I am a lost cause on that front. So why did I keep going back to TSG? It was historical fiction to me, and I do like to learn about the past, always have. So there’s that, but I think that above all I liked the developing relationship among the children, with a girl as the catalyst. Also I spent a lot of time ill in bed at that age, and it was nice to read about others in the same case. And, at bottom, it’s a good story! (Despite the fact that it was written as a Christian Scientist tract.)

A lovely post, thank you for the reminder! We moved from a small patch of grass garden to a large one with separate parts. I was about 7 and discovered this wonderful book that I could imagine was my own garden. We even had a robin and blackbird that followed my dad around!